I had not heard of Etel Adnan until I wrote about the golden age of Lebanese art in the 60s and 70s. An age which was soon tarnished as I explain in my blog. I was entranced by her use of colour and by her story when I visited a retrospective of her work in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

You can read more here. Or here.

When Etel Adnan was a girl, she went to the beach in Beirut with her mother. The sun shone, her world seemed a blaze of primary colours against the white of the sand.

It is those bold colours and the spirit of those happy times which radiate from the walls of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in Colour as Language a retrospective of the works by the Lebanese artist who died last year aged 96 which features 78 works including paintings, leporellos (pages decorated and folded concertina-style) and vibrant tapestries.

To bring an original perspective to her work and to demonstrate his influence on her work, Vincent van Gogh is not just the host but also a guest in Adnan’s show, sharing the walls of the gallery with ten of his paintings.

Curator Sara Tas has made no attempt to compare and contrast their works but rather to show the connection between the two: the shared passion for colour, their almost metaphysical empathy for the natural world and how that came to be transferred on to the canvas.

In two videos she discusses the principles of her work and its relationship with van Gogh in a way that is both articulate and, given that they were recorded shortly before her death, poignant. As she explains, her paintings are all about colour. “When I started painting I realised that when I squeezed a paint tube the colour in front of me was so intense and so pure it looked beautiful and right. I was reluctant to mix it with other colours.”

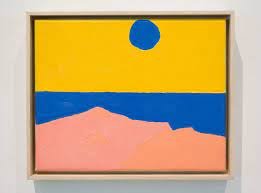

You can see the result in the deceptively simple “California” series in which her emotional impulse is expressed with direct, simple blocks of blue, red and ochre. Sometimes the mountains loom over the landscape, sometimes they seem to be fading into the horizon.

An extraordinary woman, Adnan was a poet, journalist and novelist before she was a painter. Born in Beirut in 1925 to a Syrian father and a Greek mother, she was educated in French at a school run by nuns before winning a scholarship to the Sorbonne in Paris to study philosophy. In 1955 she headed to the University of California, Berkeley, and from 1958 to 1972 taught philosophy of art at the Dominican University of California.

It was not until her thirties that she began to paint bold abstracts in the luminous colours of her Beirut childhood. Her early work was architectural — influenced by her desire as a young woman to be an architect only to be discouraged by her mother who insisted it was an unsuitable career. Her partner, the ceramicist Simone Fattal, recalled how she often began a painting with a red square as if to find the locus on the canvas and this is particularly evident in her early works. Most of her paintings were left untitled because she felt the viewers should make up their own minds what they were looking at, but the architectural influence is obvious in “Inca King” (1965), which is the only remotely figurative image on show.

Now, after years of relying on the written word, she began to express herself in her art. Her talents went unrecognised internationally — except for the Lebanese artistic diaspora, for whom she had long been an icon — until 2012, when a collection of her paintings was included in documenta, the five-yearly exhibition in Kassel, Germany. Two years later, White Cube in London staged a show of her work followed by her first retrospective at the Serpentine Galleries in 2016. The critic for The Times wrote: “I find more joy in her earlier works than her most recent geometric, reduced forms, but the show is immensely cheering.”

Her distinctive style owes something to the way she painted her works flat on a table and “attacked” the canvas, laying down the oil straight from the tube in thick, dramatic blocks of colour. The paintings were often completed in one intense session, which added to their vitality. Take her paintings from the window of her home in Sausalito, California, of Mount Tamalpais; she painted this view every day, capturing the changing mood of the mountain in strong reds, burnt orange, blues and mauves as the sun shone, the clouds gathered and the light brightened, flickered and faded.

“That mountain became my best friend,” she said. “It was more than just a beautiful mountain: it entered me, existentially, and filled my life. It became a poem around which I orientated myself.”

It is tempting to suggest that mountain was a surrogate for those sunny days of her Lebanon childhood for, despite her exile being self-imposed, she was haunted by the suffering of her country. Perhaps because she was in need of an anchor to the past, she continued to paint her mountain when she returned to live in Paris in the last years of her life.

For Adnan, colour was a direct expression of nature, a way to embrace beauty, and she considered van Gogh the first artist daring enough to apply this in his art. “He really liberated colour,” she said. “Because he accepted it as true.”

She referred to van Gogh’s “The Sower” (1888) and her own “Hot” (1960), two paintings which could hardly be more different in style - van Gogh’s earthy, rather gloomy, scene of the farmer at dusk; Adnan’s burst of colours plastered on to the canvas - her familiar squares against swirling yellows and bleached pinks.

She would argue that while she was entirely intuitive about her approach to her work, van Gogh had a more questioning relationship to nature and spent much of his early years studying theory of art. He painted what he could see, she painted what she felt, but, she says of the two paintings, there is an awareness that nature is ‘like an architect - which organises itself and creates lines of force.’

There is perhaps one scenario where the curator makes a comparison between the two. Opposite the dramatic tangled skein that is Sunny Swamp is van Gogh’s Tree Roots, but while Adnan’s work is full of life and energy van Gogh’s is dark, the roots writhing in a reflection of his tortured frame of mind. It was his last painting before his suicide.

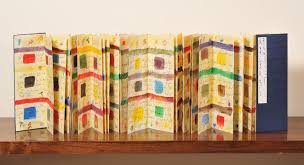

With Adnan, words and paintings were intermingled — “I write what I see, I paint what I am” — and language met illustration in her leporellos, delicate paper concertinas on which she added drawings to illustrate? the verses of Arab poets or to lament the turmoil in the Middle East. Because of her upbringing in a European school, she never learnt Arabic properly so had her English translated into Arabic characters, which she then drew.

One of the most arresting leporellos is “Journey to Mount Tamalpais”, in which a poem in praise of the mountain is set against sketches of it and multicoloured stripes that seem to speak to the rhythms of the day and the changes in the seasons.

The exhibition ends with “The Weight of the World”, a series of small paintings set in a straight line across one gallery wall, each with an orb suspended in space. This is the sun as an expression of the infinite, suggesting the vulnerability of the Earth and the people in it. It’s affecting, calming. Even the gallery’s carpet is wittily designed, with circular yellow seats to reflect the paintings and enhance the effect of tranquility. In fact, the curator invites the viewer to lie down on the carpet and meditate.

Adnan would have approved. In one of the video interviews, she talks about the way she looked at beaches and fields and recognised that there were ‘powers in the world and they organise themselves’.

“Landscape is not separate from our cosmic awareness,” she said. “We are in nature, we are not alone. Nature is strong and it attracts us. We look for beauty. It makes us happy. It’s not complicated, we need it.”