This piece should have appeared in The New European a month ago but, well, who knows why, it didn’t appear. Timely though. Always will be.

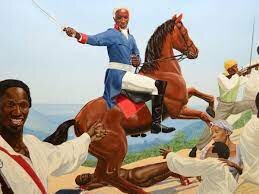

Every generation has to have its heroes. Military leaders, explorers, politicians. Mostly men and men of action at that. A few poets and writers are allowed to perch on a plinth. The occasional sporting hero. In fact, David Beckham was suggested as an appropriate candidate for the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square.

From ancient Egypt, the Mayans, Greeks and Romans, statues, monuments, stelae and triumphal arches have been raised for the populace to admire. The Victorians could hardly see a street corner or some public edifice without sticking up a memorial to a national hero or local worthy.

There they stood for decades, invariably unchallenged, until now when there is hardly a statue in the western world which is not under scrutiny. Pull down and destroy those with a shameful past? Hide away in a museum basement? Leave upright - with a note of explanation tacked to its plinth?

Boris Johnson insisted that removing statues of controversial figures was to lie about our history after the statue of Winston Churchill on Parliament Square was daubed by Black Lives Matters protesters but historian David Olusoga, on the other hand, argues that it is ‘palpable nonsense’ to say that their removal somehow impoverishes history. Indeed, failure to get rid of them is a validation of people who did ‘terrible things'.

Sometimes it’s an easy decision. No one would defend the obliteration of all traces to do with Jimmy Savile. But when activists vandalised the statue Prospero and Ariel by paedophile and dog lover Eric Gill which stands outside Broadcasting House, the BBC did not agree it should be removed with some art critics arguing that Gill’s artistic genius trumps his failings as a human.

That’s where the problem lies. Standards, morality, what is wrong and what is right, have changed so much over the centuries - and will continue to evolve - that the only person who could have a statue without fear of naming and shaming 100 years from today is the late Barry Cryer.

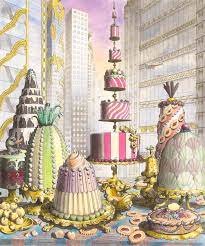

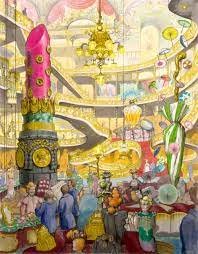

So what to make of it all? In Testament, a small, but congested exhibition at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art in South, London, several contemporary artists are having a go.

According to the booklet which accompanies the exhibition - and helpfully tracks the works around the walls - the artists were invited to consider what is at stake in tearing down and erecting monuments.

‘Are they (monuments) defunct, illusory statements of permanence, continuity, and manifestations of power? Whose narratives do they preserve, and whose do they suppress? Can they still play a vital role in mediating communal grief and providing a locus for memory? Is there space for them to be re-envisioned?’

Several important names have contributed to the debate using sketches, installations, sculptures, paintings and films such as Phyllida Barlow, Ryan Gander, recently made a Royal Academician, Roger Hiorns, and Turner Prize winners Jeremy Deller, Laure Prouvost, Mark Wallinger and Oscar Murillo.

Do they meet the criteria set out in the exhibition guide and meet the challenge directly? Not really. But the subjects they choose and the style they use to express them are often implicitly answers in themselves.

First off; there are no statues to individuals. No personality cult here. Instead causes and concerns are featured such as migration, racial awareness and the environment. One or two address man’s inhumanity to man and political corruption. Surprisingly, there are no references to the predicaments of the LGBT community which so preoccupies much of contemporary cultural debate.