I spent the best part of three months in Venice some years ago. How little has changed - superficially at least - and how much transformed for the worst. Read more:

Zen and the art of a painting a picture.

Pull 'em down. Keep them up. Think again

This piece should have appeared in The New European a month ago but, well, who knows why, it didn’t appear. Timely though. Always will be.

Every generation has to have its heroes. Military leaders, explorers, politicians. Mostly men and men of action at that. A few poets and writers are allowed to perch on a plinth. The occasional sporting hero. In fact, David Beckham was suggested as an appropriate candidate for the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square.

From ancient Egypt, the Mayans, Greeks and Romans, statues, monuments, stelae and triumphal arches have been raised for the populace to admire. The Victorians could hardly see a street corner or some public edifice without sticking up a memorial to a national hero or local worthy.

There they stood for decades, invariably unchallenged, until now when there is hardly a statue in the western world which is not under scrutiny. Pull down and destroy those with a shameful past? Hide away in a museum basement? Leave upright - with a note of explanation tacked to its plinth?

Boris Johnson insisted that removing statues of controversial figures was to lie about our history after the statue of Winston Churchill on Parliament Square was daubed by Black Lives Matters protesters but historian David Olusoga, on the other hand, argues that it is ‘palpable nonsense’ to say that their removal somehow impoverishes history. Indeed, failure to get rid of them is a validation of people who did ‘terrible things'.

Sometimes it’s an easy decision. No one would defend the obliteration of all traces to do with Jimmy Savile. But when activists vandalised the statue Prospero and Ariel by paedophile and dog lover Eric Gill which stands outside Broadcasting House, the BBC did not agree it should be removed with some art critics arguing that Gill’s artistic genius trumps his failings as a human.

That’s where the problem lies. Standards, morality, what is wrong and what is right, have changed so much over the centuries - and will continue to evolve - that the only person who could have a statue without fear of naming and shaming 100 years from today is the late Barry Cryer.

So what to make of it all? In Testament, a small, but congested exhibition at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art in South, London, several contemporary artists are having a go.

According to the booklet which accompanies the exhibition - and helpfully tracks the works around the walls - the artists were invited to consider what is at stake in tearing down and erecting monuments.

‘Are they (monuments) defunct, illusory statements of permanence, continuity, and manifestations of power? Whose narratives do they preserve, and whose do they suppress? Can they still play a vital role in mediating communal grief and providing a locus for memory? Is there space for them to be re-envisioned?’

Several important names have contributed to the debate using sketches, installations, sculptures, paintings and films such as Phyllida Barlow, Ryan Gander, recently made a Royal Academician, Roger Hiorns, and Turner Prize winners Jeremy Deller, Laure Prouvost, Mark Wallinger and Oscar Murillo.

Do they meet the criteria set out in the exhibition guide and meet the challenge directly? Not really. But the subjects they choose and the style they use to express them are often implicitly answers in themselves.

First off; there are no statues to individuals. No personality cult here. Instead causes and concerns are featured such as migration, racial awareness and the environment. One or two address man’s inhumanity to man and political corruption. Surprisingly, there are no references to the predicaments of the LGBT community which so preoccupies much of contemporary cultural debate.

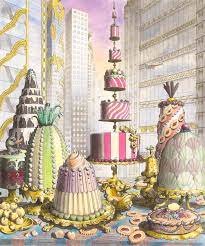

Sojourners Settlers Sponge by Jay Tan

Jay Tan’s suggestion is a giant cake. In Sojourners Settlers Sponge she celebrates the Chinese immigrants who settled in East London at the turn of the 20th century with a maquette of a cake extravagantly decked with ribbons, fake flowers, bangles and sweet wrappers. She wants to see a full sized version in the middle of Limehouse where the first Chinatown was born.

Well, it could be fun, though any number of weight-watching protest groups will rally against such an unhealthy symbol.

On the other hand Rabiya Choudhry combines fun with practicality in The Lost Ones, a 14ft candle gaudily decorated with candy-coloured stripes and a beaming candle atop. She explains that it is a testament to all the people that have lost loved ones or feel lost in the world but also for women like herself who feel unsafe walking through streets at night. The lamps will guide them home.

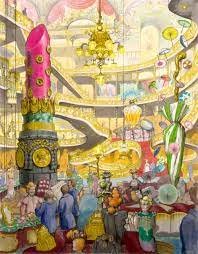

Monument for Oxford Circus by Tenant of Culture

The failings of capitalism are targeted by Tenant of Culture, aka Dutch artist Hendrickje Schimmel, who highlights the waste and poor working conditions which blight much of our consumer society. His Untitled (monument for Oxford Circus) is a proposal for a patchwork, 30 metres high by ten wide, of used trainers which he envisages being hung from a building in Oxford Circus where they will take 200 years to decompose as a mouldy, smelly, eyesore.

Rather than one symbol to aggrandise an individual Oscar Murillo has assembled plastic garden chairs, and loaded them up with lumps of bread made of corn and clay to create Collective conscience. The chairs evoke community and family gatherings, a spirit which he argues has been lost along with their working classes

With typical look-at-me bravura Monster Chetwynd has come up with A Monument to the Unstuffy and Anti-Bureaucratic, a vast comic-cut monster with gaping teeth made of latex, foam and paper. It’s meant to be a monument to ‘authenticity... Radical laughter and nonsense and spontaneity.’ It seemed to have worked in that respect - two children happily played in the creature’s mouth.

Ghislaine Leung has made an inflatable pub. It’s amusing but what else? Does it meet the dictionary definition of the word testament which gives the exhibition its title: Something that serves as a sign or evidence of a specified fact, event, or quality? It was created in 2021 so maybe it is a monument to all the days we couldn’t go to locked down pubs but does it challenge the relevance of statues as posited in the exhibition’s statement of intent?

Like Chetwynd, probably not.

What does challenge our perception and what it could or should represent is a brutal work by Phyllida Barlow - Untitled: hostage; 2022. It doesn’t seem much more than two chunks of wood supporting what looks like an upturned plastic bag.

You have to read the transcript alongside. It recalls a conversation taking place between a film maker, Barlow and an Iranian student while they watch an horrific account of a woman being stoned for her adultery in Iran. The victim is shrouded, wrapped and tied up and pushed into a hole when the crowd is commanded to stone her.

Phyllida Barlow

By the end it is almost impossible to identify her body from that heap of mangled, bloodied rags.

Look again at the sculpture. The two pieces of wood are blood-stained stumps of legs. The plastic bag becomes a shroud to hide her battered head. A football takes the place of her battered head, adding a grotesque horror to the scene.

It is hard to imagine this set high on a plinth as a testament to such evil. Perhaps it should be.

While many of the offerings on display take the form of a physical entity - like the statues so loved by the Victorians - as might be expected the stone and bronze of tradition is often replaced by the video and installation of the 21st century.

Adham Faramawy has made an engaging video A proposal for a parakeet’s garden using the birds as symbols of migrants, often displaced by colonial forces, arriving in a country where they are not universally welcome - just like the influx of the birds in recent years which many claim is affecting the local avine population. ‘Wherever they fly, let them come,’ runs the commentary.

Just as appealing visually, just as serious, is Scott King’s Total Floralisation (zone: 023), which argues that covering streets in flowers and plants not only helps the environment but makes hitherto run down streets places of beauty which people would actually want to visit. But more, such efflorescence would help fight poverty as visitors are attracted to such an attractive spot, shops would flourish once again and cafés prosper.

These are understated works, pleasing to the eye and quietly forceful, which cannot be said for Dominic Watson’s strikingly vulgar work England, Their England. Made of papier maché, with added water pumps and wine, it is inspired by the satirical suggestion that each prime minister has to undergo colonic irrigation when he leaves office to purge himself of the misdemeanours committed when in power. He portrays the enema being enthusiastically expelled by the Flusher and willingly lapped up by an eager John Bull character, the Flushee.

It’s crudely funny - disgusting, in fact - but Watson is angry: ‘Democracy at this moment in time presents itself to us in the form of an Eton education and well-cut accent, but that’s not how it feels. It stinks. It’s rancid, it’s insidious. I want the monument to subvert that and evoke a sense of disgust.’

(He had in mind an earlier old Etonian Prime Minister but it’s hard to assume he would not include the present incumbent as worthy of that assessment).

Should he want to plonk his work on a plinth, there is one to hand in the exhibition. Olu Ogunnaike has made a maquette I’d rather stand which is a copy of Trafalgar Square’s empty fourth plinth made of unused, rubbishy, bits of wood veneer collected from dusty factory floors and reworked to cover ‘one of the few monuments that are seemingly dedicated to nothing.’

Given that the other three plinths are occupied by such titans of British history as the notoriously dissolute King George lV and two Victorian generals, one who fought in the disastrous Afghan War and another who laid waste great tracts of India, this could be just the spot to dedicate to Flusher and his obliging Flushee .

Magnificence, misery and mischief

Our appetites for travel were sharpened by the years of lockdown because we could not go anywhere. In the 18th and 19th centuries the wealthy - invariably the wealthy - wandered elegantly around Europe, occasionally hindered by plagues, sometimes by war and even an exploding volcano.

They cannot stop us

It seemed somehow incongruous to run this piece without mentioning the small matter of the war on Europe’s borders, especially as the thousands of Ukrainians are making their melancholy way towards the west.

But the problem of the refugee still remains around the world and the iconography of the wall remains as potent as ever.

This is the piece the European published. Read here:

This is a companion piece they did not find room for. Berlin Voids by photographer Paul Raftery.

While Rafał Milach used the symbolism of chunks of the wall the wall to investigate its legacy English photographer Paul Raftery went for a walk.

In Berlin Voids, a series of images taken for an exhibition in 2014, he found that many traces of the wall in the city centre had been built over, such as in Potsdamer Platz with its underground station and Ritz Carlton Hotel. The further he wandered from the centre he discovered how the death strip had become a place for relaxation and sport where horses grazed, sunbathers dozed and walkers followed a well trodden path to a lake where before they would be shot if they went close.

What he found on a return visit this summer for a book project was that the land grab in the centre had intensified in areas such as Kreuzberg where real estate values have become too inviting to resist and buildings such as the vast black and glass offices of Axel Springer's German media empire bestride the course of the wall.

The use of the death strip as a place for leisure has also increased. In the spirit of New York’s urban walkway, the Highline, a riverside walk in the centre follows the curve of the river which had once been cut off by the wall and further afield he encountered Berliners on walks through forests where thousands of silver birches have been planted and whizzing along on electric bike tours, tending bees and taking up hobbies such as training falcons.

Raftery only revisited one scene; two blocks of flats side by side. It was obvious in 2014 that the house on the right had been in the East, shabby, boarded up and with rusting balconies. Now it is so smart it even boasts a trendy wine bar while its neighbour in the West is the scruffy one, disfigured by graffiti. The strip of land between them remains the same.

As for legacy, although many of the voids have been filled, the ghost of the wall lingers.

“I think Berlin has difficulty in dealing with its monuments because everything is laden with their 20th century history,” says Raftery. “They don’t want to rehabilitate everything and they don’t want to destroy everything because that would lead to all sorts of accusations, so they just let things disintegrate

“So the solution is to be pragmatic; ‘let’s not formalise too much, let some relics of the past disintegrate but use the places that are open as a resource for the city.’”

After and before

Strife between islands - or oceans apart

I’ve always been drawn to the West Indies - not for the sun or the cricket team ( though they are both major attractions) but because I was born in Jamiaca. It’s a flimsy relationship, I admit, but I was pleased - amazed - that my first home up in the Blue Mountains above Kingston is still there. The exhibition Life Between Islands is an, often bitter, portrayal of the fate of the Caribbean immigrants who came over on the Windrush in the 50s and 60s. Terrific painting, demanding videos. Read more

Moel shoot in Brixton

Schoolgirls with provocative satchels

Hell of a show

Extraordinary exhibition at the Soane’s Museum of the imaginings of Pablo Bronstein. There’s a method in the madness.

Knock, knock, are there any artists there?

One of the odder shows of the year but one of the most intriguing - the world and works of the spiritualist artist.

Madonna-like figure by Anna Mary Howitt

On the crest of his wave

Marvellous exhibition at the British Museum on the Japanese artist Hokusai. Real treat.

Read more in The New European

What's in a title?

Black art matters - of course it does - but was this the best way to make the case? I walked, I looked, I wondered…

Read more in The New European

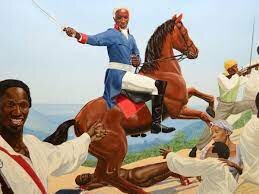

Touissant L’Ouverture at Bedourette by Kimathi Donkor

Larry Achiampong

Evan Ifekoya’s Ritual Without Belief

Dark waters

The walk from the mouth of the Thames, well, all right, from the flood defying barrier takes you through untidy London suburbs, shiny new - often empty - high rises and on into fields and floods. It has to be done. I managed it as far as Oxford spread over several months. Until I attempt the rest this marvellous set of images will more than compensate.

Prayers and play in Southend

The Mayflower settlers: brutish colonialists? Seekers after a free world? What is the truth?

When the 350th anniversary of the Mayflower voyage was celebrated in 1970 a spokesman for the Wampanoag tribe on whose territory the settlers had landed was invited to give a speech.

At the last moment he was excluded because the organisers ‘didn’t like what he had to say.’ He had planned to tell the world that the Wampanoag were part of the Mayflower story and should be recognised as such. And so they should. The tribesmen could easily have driven off the interlopers, half of whom died within five months of landing in November 1620, but instead, they made peace, they showed the settlers how to survive in that alien landscape, grow corn, catch fish and ensure their first harvest.

The long-delayed expression of their grievances was to be central to an ambitious ceremony planned for Plymouth, Devon, where the Mayflower docked briefly before sailing to America in September, 1620. Postponed last year and rescheduled for July 10-11 - only to be kiboshed again by Covid.

You would imagine universal disappointment at the news but not so. Take this acerbic tweet from @MayflowerLondon, one of the many significant players in the anniversary celebrations: ‘Great news that the awful M400 Ceremony has been cancelled. Focussing M400 celebrations on Plymouth Devon distorted the history of Britain.’

The reason for their hostility? For many - and for me who spent five years writing Voices of the Mayflower which is out now - the story has become, not about the Mayflower, not about the settlers, but about the Native Peoples.

The re-writing of history has been under way since that snub in 1970, shared and encouraged by the governing body, the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, and reinforced months ago when the original anniversary plans for the UK were announced.

Jo Loosemore, director of the Plymouth museum The Box, declared that the need to examine ‘difficult history’ was central to a ‘major exhibition looking at the controversial history of British colonisation.’ Myths would be debunked - though the publicity did not spell out what they were. She and Mayflower 400, the umbrella group organising events across the country, were advised by Wampanoag activist, Paula Peters, who described the collaboration as a chance to tell ‘a story that has been marginalised for centuries’.

But it is the Mayflower settlers who have been marginalised. More, many descendants, proud of their heritage, consider that the narrative of their ancestors’ audacious voyage has been hijacked.

The Box’s pre-pandemic publicity enthused about its exhibition, Mayflower 400: Legend & Legacy with its array of Mayflower-related artefacts but the headlines were about a Wampanoag ceramicist who was to make a cooking pot based on a traditional design and there was great enthusiasm for a ‘fully decolonised art and events programme’ presented by 29 Native American artists from New Mexico. (Not a destination on the itinerary of the 1620 voyagers).

Much was made of a wampum belt made of shells from the New England sea shore as a symbol of the spirit and culture of the indigenous peoples. What the publicity did not explain was that wampum, more prosaically, was used as a currency by Europeans and Native Peoples alike and as the settlers’ governor William Bradford wrote: ‘It makes the tribes hereabouts rich, powerful and proud and provides them with arms and powder and shot...’

That small piece of knowledge brings some balance to the inference that the Wampanoag culture was snuffed out by exploitative colonialists.

Nevertheless, the official position was that the Wampanoag had been ‘excluded from the narrative... despite having been devastatingly affected by colonisation due to the Mayflower's arrival and subsequent European settlement.’ The indigenous people ‘eventually saw their lands and homes brutally taken from them and ultimately the slaughter of their proud people.’

Well, let’s look at those statements. One claim is that disease spread by the settlers killed off the Native Peoples. Not so. It was spread by different explorers some three years earlier.

Devastatingly affected? When the settlers arrived the land was deserted. They did not fight for it, or seize it. Even years later, as the settlement in new Plymouth expanded its borders, they bought the land from the Wampanoag.

Paula Peters, the anniversary adviser, once declared: ‘The goal (of the Mayflower incomers) if not to annihilate was to assimilate (the Wampanoag)’ but there were negligible hostilities between the English and Wampanoag apart from a brief flurry of gunshot and arrows when they first landed. Furthermore both parties signed a peace treaty in March, 1621, which lasted for more than 50 years. It was only then that the all-out assault on the indigenous people began and it was led by a different group of settlers.

This idea of a colonising force, so casually bandied about, is preposterous when you realise that the Mayflower sailed short of weapons -‘nor every man a sword to his side,’ grumbled Bradford. Furthermore, the voyagers were made up of families with almost as many women and children as men on the ship. Not the most effective force to annihilate even the feeblest of foes.

So how have we reached this alternative version? It seems clear that centuries of justified rage at the genocide of their people, disgust at slavery - though there is no evidence that the settlers used forced labour - has been conflated and attributed to the settlers. And what better time than an anniversary to promote that message?

How was that anger, that need for reparation, to be reflected by Mayflower 400? Before Covid struck, plans had been made to hold an ‘unforgettable weekend (on July 10-11) of music and dance fusing hip-hop with an evening of live music, choirs and schools’.

Well, it might have been fun. It was also hilariously inappropriate. One can only imagine what Governor Bradford and his pious settlers would have made of it.

This was the man who sent a band of armed men to destroy a rival English settlement because they were ‘quaffing and drinking both wine and strong waters in great excess. They also set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing aboute it, inviting the Indian women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together.’ This is also the religious diehard who broke up a Christmas party because ‘there should be no gaming or revelling in the streets.’

He might have been perplexed by the Mayflower 400’s plans for Plymouth which have survived, including a giant puppet in the form of a dragon which is destined to roam through the city and distinctly unamused by a comedy play which considers important Mayflower-related issues such as, ‘why do our American friends call trousers pants?’

It’s not as if there cannot be fitting commemorations. Talks, walks and festivals are going on from Chorley Lancs, to Southampton, from Shrewsbury to Harwich, in Dorking and in Dartmouth. A flotilla sailed up the Thames recently on the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower’s return to Rotherhithe and in Scrooby, Notts, a festival will be held in the manor where many of the dissidents who inspired the pilgrims gathered in the late 16th, early 17th, centuries.

But the enterprising Bassetlaw Museum in nearby Retford has also been beguiled by the Wampanoag story and plans to demonstrate the building of a traditional Indian dwelling. Educational, interesting, but how about telling how the half a dozen able-bodied settlers managed to wrest homes out of the wilderness during the first winter as half their number fell dying amongst them?

But let’s not be spoil sports like the stern Bradford. What about the formalities - the speeches, the appeals to the core values of freedom, humanity, imagination and the future which were to be extolled during the revelries?

In the publicity, much was made of leading representatives of the Wampanoag taking part. All right and proper. But there was something - or rather someone - missing. Although, ‘high-ranking dignitaries’ were to speak, there was no mention of a Mayflower descendant being included, and despite me asking twice, no one was able to confirm that anyone from Plymouth, Massachusetts, home of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, was attending. In fact, one leading light in the Mayflower community had made her own arrangements only to have her plans thwarted by quarantine regulations.

There are 30 million or so Mayflower descendants scattered around the world and a few thousand Wampanoag in New England. They both deserve to have their voices heard.

Richard Holledge is author of Voices of the Mayflower, out now.

We know that Britain was the most enthusiastic colonial power when it came to slavery but others were not far behind in perpetrating this vile trade as an unflinching exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam demonstrates.

Paulus, the possession

The Oopjens

Let's get phygical

We’ve become so used to not going anywhere that it seems counterintuitive to suggest that now that the doors are opening we visit galleries virtually rather than in the flesh. But on the other hand…

Meet the Nutters and other curious folk

There’s nowt so queer as folk and photographer Homer Sykes has proved that over the years. Here’s a jolly romp through curious customs which, surprisingly, continue to this day. Read more in The New European:

The Nutters!

The Marshfield Mummers

Drinks for the Burry Man

The making of a saint

Areal-life tale as dramatic as Game of Thrones... with drama, fame, royalty, power, envy, retribution, and ultimately a brutal murder that shocked Europe. The murder of Archbishop Thomas Beckett commemorated in fine show at the British Museum .

Scents and sensibility

The idea of paintings which you can smell was, er, not to be sniffed at. Here’s a piece on a show staged at the incomparable Mauritshuis in Den Haag, the Netherlands. In The New European, April 2021.

Read: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/brexit-news/europe-news/art-you-can-smell-7884712

Pop goes the artist; Why Richard Hamilton was so important

Inevitably postponed by the pandemic this show at the Pallant, one of my favourite galleries, opened briefly only to be closed until… well, until when?

Meanwhile, read all about it.

Just what was it that made yesterday’s homes so different, so appealing?2004

Soft Pink….

The critic laughs

Peake practise

It can be Grimm in Gormenghast

Let's hear it for the Mayflower mothers

This piece appeared online in the Daily Telegraph. It was due to appear in print but the new line up for Bake Off took precedence. The pilgrim mothers would have known how to cook honey cakes and make syllabubs but I don’t suppose there was much baking on the Mayflower.

Everyone has heard of the Pilgrim Fathers. Doughty, God-fearing souls who sailed to America on the Mayflower to create a world where they could follow their religious beliefs without fear of persecution.

But what makes the voyage remarkable are the mothers, the unsung heroes who sailed alongside their men on the momentous enterprise which began in July 400 years ago.

There were 18 women and of those, ten took their children with them. Incredibly, given the tumultuous adventure they were about to undertake, three were pregnant and another breast feeding her infant. Just as startling, there were more than 30 children and youngsters under 21 years old on the ship.

As for the men - the husbands, single men and servants - they totalled 50 in all and were actually outnumbered by the women and their offspring.

That the role of women in the story is scarcely acknowledged is perhaps unsurprising given that 17th century females invariably owed their status and identity to their men folk. Unsurprising too, that the accounts of the historic voyage are by men about the men, not least by William Bradford, who became governor of the new settlement in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

He did, however, acknowledge that the ‘weak bodies of women’ might not withstand the rigours of the journey though he could not foresee just how deadly the undertaking would be.

The arrangement was for the self-styled pilgrims to sail on the Speedwell from Holland where they had lived in exile from English persecution for 12 years and rendezvous with the Mayflower in Southampton. The Mayflower, meanwhile, left Rotherhithe, London, carrying 65 fortune seekers who had financed the expedition and hoped to recoup their investment by making their riches from the flourishing New England beaver trade. The two groups were to sail convoy across the Atlantic but the Speedwell became as 'leakie as a sieve’ and was abandoned in Plymouth, Devon, at which point many of the pilgrims joined the crowded Mayflower.

The ship, which had been used for the cross-Channel wine trade, now had 102 passengers thrust cheek by jowl in the stink of the hold, forced to endure the lack of hygiene, the smell of unwashed bodies and the grime of filthy clothes.

Privacy was impossible. To relieve themselves the voyagers had to balance precariously on the ship’s bowsprit but in storms they stayed below decks and used chamber pots which were sent flying across the cabins when the waves hit and the winds rose.

As for food; a niggardly diet of salt meat, peas, hard tack biscuits which became infested with weevils and to drink, beer. No wonder the hold became a breeding ground for lice and scurvy.

Not until the Mayflower dropped anchor off Cape Cod on November 11, 1620 - more than 100 days since leaving Southampton - were the women, at last, able to step on to land and wash their clothes ‘as they were in great need.’

Remarkably only one of their number died on the voyage but two soon followed after making land and a few weeks later Bradford’s wife Dorothy fell from the ship’s deck into the chill waters of the bay. Her body was never found. Strangely, Bradford records the death only in the appendix to his writings with a terse: ‘Mrs Bradford died soon after their arrival.’

Was he as indifferent as he seems? She was only 16 when they married and he 23 and she had been compelled to leave their three-year-old boy behind. Was she so desolate at being separated from him that she committed suicide? In truth, no one knows what happened that bleak winter’s day.

But what time could there be for private grief when cold, disease and hunger took away half the settlers in the first three months after landing? As they struggled to hew a settlement out the wilderness they were too enfeebled to resist scurvy - first the symptoms of putrefying ulcers and bleeding gums, then diarrhoea, fever and death.

The women suffered a far higher percentage of fatalities than the men or children. Only four mothers survived the first winter, not so much because of their ‘weak bodies’ but because the men were out in the fresh - if freezing - air, building their new homes, while the women were confined on the Mayflower for a further four months. In those close confines the disease spread quickly, especially as the women exposed themselves to danger caring for the sick and dying.

The death toll was remorseless. Of the pregnant trio who set sail, Elizabeth Hopkins, gave birth to baby boy Oceanus in mid-Atlantic, adding to the three children who sailed with her. Mary Allerton, who already had three children under seven, suffered a still-born birth and died within days. Sarah Eaton, who had been breast feeding her son, also perished, leaving the infant to be brought up by her husband.

And, as if in affirmation that among the saintly there are trouble makers, Eleanor Billington, who had two rowdy boys and years later witnessed the execution of her husband for murder, became notorious for her sharp tongue and was found guilty of slander, strapped in the stocks and whipped.

Perhaps no survivor had a more harrowing experience than Susanna White. Soon after the arrival she ‘was brought a-bed of a son which called Peregrine’ - the first child to be born in the new world and a brother to her five-year-old son. Her happiness was short lived for within weeks her husband William died. Yet on May 12, eleven short weeks later, she married fellow passenger Edward Winslow, a leading light in the movement, who himself had been widowed as recently as March 24.

Widowhood and remarriage were routine in those days of shortened life expectancy - of the 13 couples on the voyage four were second marriages - but this surely was no love match. Instead, they accepted that they had to sacrifice their own feelings for the good of the settlement which needed children to survive. Susanna had three boys and a girl. Her duty was done.

Of the four mothers left alive Mary Brewster, who at 52 was the matriarch of the new community, brought two of her four children. She was typical of a female who played a major part in the saga but is fleetingly mentioned while her husband William was - quite rightly - lionised as a pilgrim hero. But how much did he owe to the woman who supported him when they fled persecution in England in 1608 and through the years of exile in Holland? We are not told.

It was the generation of younger women who helped ensure the colony lived on. Six girls were orphaned in the first deadly winter and two were to marry fellow passengers. Their names, Elizabeth Tilley and Priscilla Mullins, are unknown to all but the most familiar with the Mayflower story but they had ten children each and their resilience and hard work were essential to the prospering of the settlement. Although there were other marriages and many more children, their legacy lives on in their descendants which include six US presidents.

All told 30 million US citizens can trace their heritage back to the Pilgrim Mothers.

Picture: artist’s impression of the first thanksgiving. Women doing all the work!

Review from the New European. The timing was a little awry but I have to agree with the sentiments!

Voices of the Mayflower by Richard Holledge

July marks the 400 years since a motley bunch of people sailed across the Atlantic to the New World on a surprisingly small tub called the Mayflower. Among the many books and programmes commemorating the anniversary few will have the human insight of this, in which Holledge brings the voyage to life with an account that is not quite fact but not completely fiction either. As ever the best history is told though individual stories and Holledge’s imagined voices speak to us eloquently down the centuries.’

Voices of the Mayflower by Richard Holledge is out now